Not to be missed! A major exhibition entitled, Orchestrating Elegance: Alma-Tadema and Design is presently underway at the Clark Museum in Williamstown, Massachusetts, but only until September 4th.

by Michael Djordjevitch

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema: Preparation for Festivities (1866) Source

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912) is justly celebrated for his peerless painterly evocations of the Ancient and Medieval Worlds.

Alongside the above exhibit on our shores, another exhibition, Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity, which includes more than one hundred works, has recently opened in London, at the Leighton House Museum, and will remain open until the 29th of October 2017.

Together these two exhibitions reintroduce Alma-Tadema the serious artist to the contemporary scholarly art world. As evidenced by countless calendars and posters, Alma-Tadema has long been popular with the general public. It is only recently, with the developing interest in the works that the artistic avant-garde of the early to mid-twentieth century rejected, that mainstream nineteenth-century art has again become an object of academic interest and study.

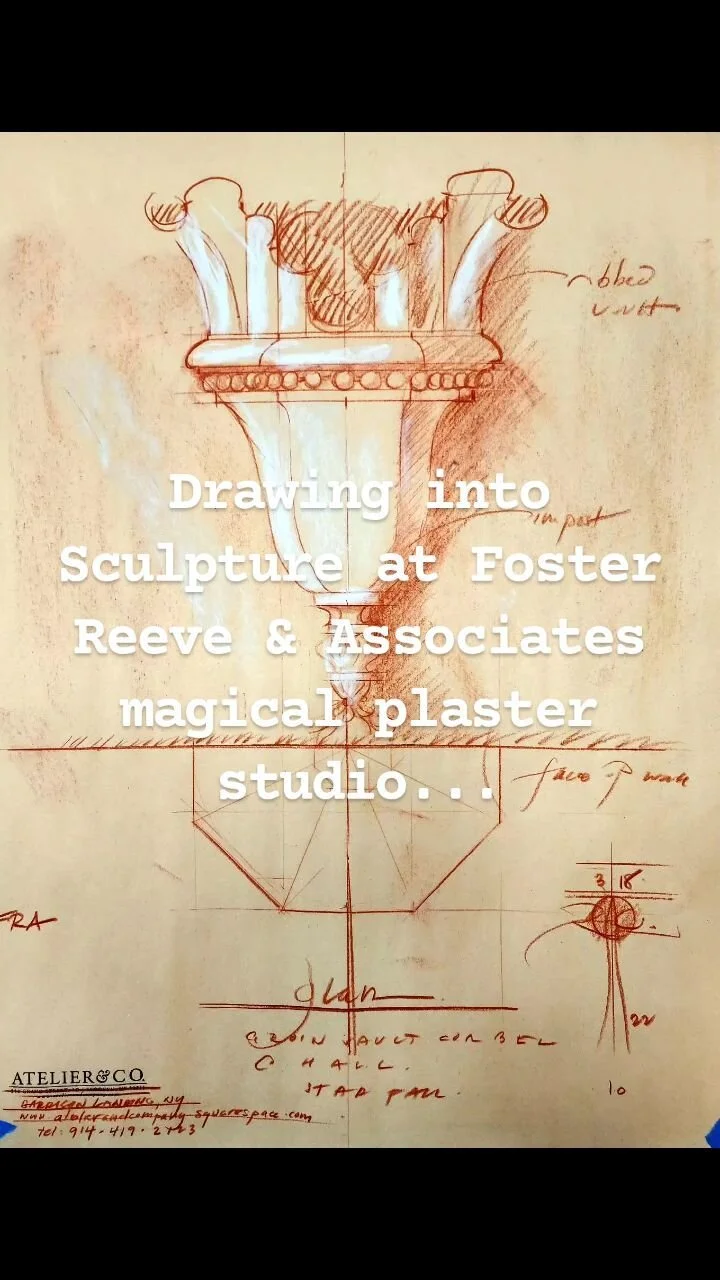

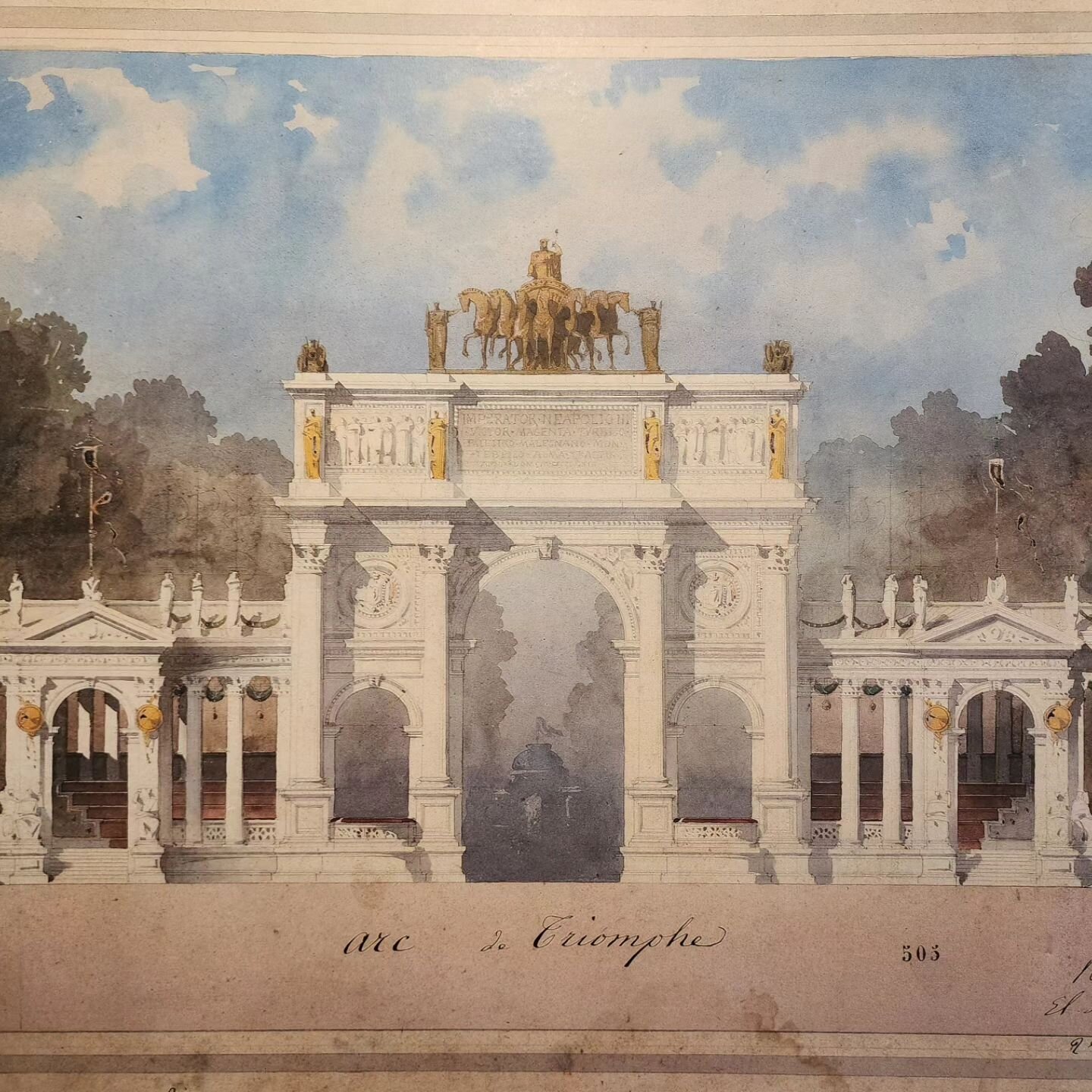

The exhibit in Massachusetts is unique because it focuses on works that are all related to one another. Originally they belonged to a music room in a fifth-avenue mansion, commissioned in 1884 by New York magnate and philanthropist Henry Gurdon Marquand (1819–1902).

Source

Marquand’s Music Room had two foci.

The one that is far more familiar to us today is a painting by Alma-Tadema, A Reading from Homer. It is now part of the permanent collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and is presently on loan to the Clark for this exhibit. This was the work of art around which the Music Room for Henry Marquand was envisioned and designed.

The second is sui generis, a Steinway Grand Piano the Furniture Gazette in 1887 called, "one of the most superb specimens of elaborately artistic workmanship it has ever been our good fortune to see." This work too is Alma-Tadema’s artistic achievement.

Source

The music room of a great house was both the heart of family musical life and a stage for public musical events. And the heart of such a room in the nineteenth century was its grand piano.

Alma-Tadema turned his grand piano into the quintessential grand. Through his art he made it appear what it was meant to be, the instrument of instruments. This piano would come to be played by celebrated pianists and composers and would accompany many famous performers.

It is noteworthy that our artist, who through his assiduous studies had achieved a peerless command of the ornamental repertoire of the ancients, from the smallest objects to paintings, sculptures, furniture and architecture, chose not to conjure up an ancient-looking instrument. Rather, Alma-Tadema employed that ancient ornamental repertoire to both embellish and transform the monarch of nineteenth century instruments into a monumental entity, while allowing it to also remain recognisable as a delightfully performable grand piano.

For more images of this piano : images

For hearing and seeing the piano in performance : in performance.

Another indispensable element of a great nineteenth-century room was its deployment of fabric. Below is an image from the MET collection of one of Alma-Tadema’s surviving fabrics from this room. Note the masterly use of the classic Acanthus Scroll motif which the artist appropriates and magically makes his own.

Alma-Tadema invited a number of his fellow artists to collaborate on this music room. While the ensemble is the fruit of this vital collaboration, Alma-Tadema remains very much its designer, and thus the architect of the whole.

Alexis Goodin’s and Kathleen M. Morris’s Orchestrating Elegance: Alma-Tadema and the Marquand Music Room is a comprehensive and authoritative study of the room he made.

In New York the Metropolitan Museum remains one of the lasting beneficiaries of Henry Marquand’s philanthropy, as he was one of its original founders. Throughout his life Marquand gave many works of art to our continent’s foremost museum.

Henry Marquand’s music room was not Alma Tadema’s sole interior, nor was it his only work of architecture. Each of his two London town houses were made to his designs. Mary Eliza Haweis, in her Beautiful Houses of 1882, observed of the Townshend House: “It is essentially individual, essentially an Alma-Tadema house, in fact, a Tadema picture that one is able to walk through.”

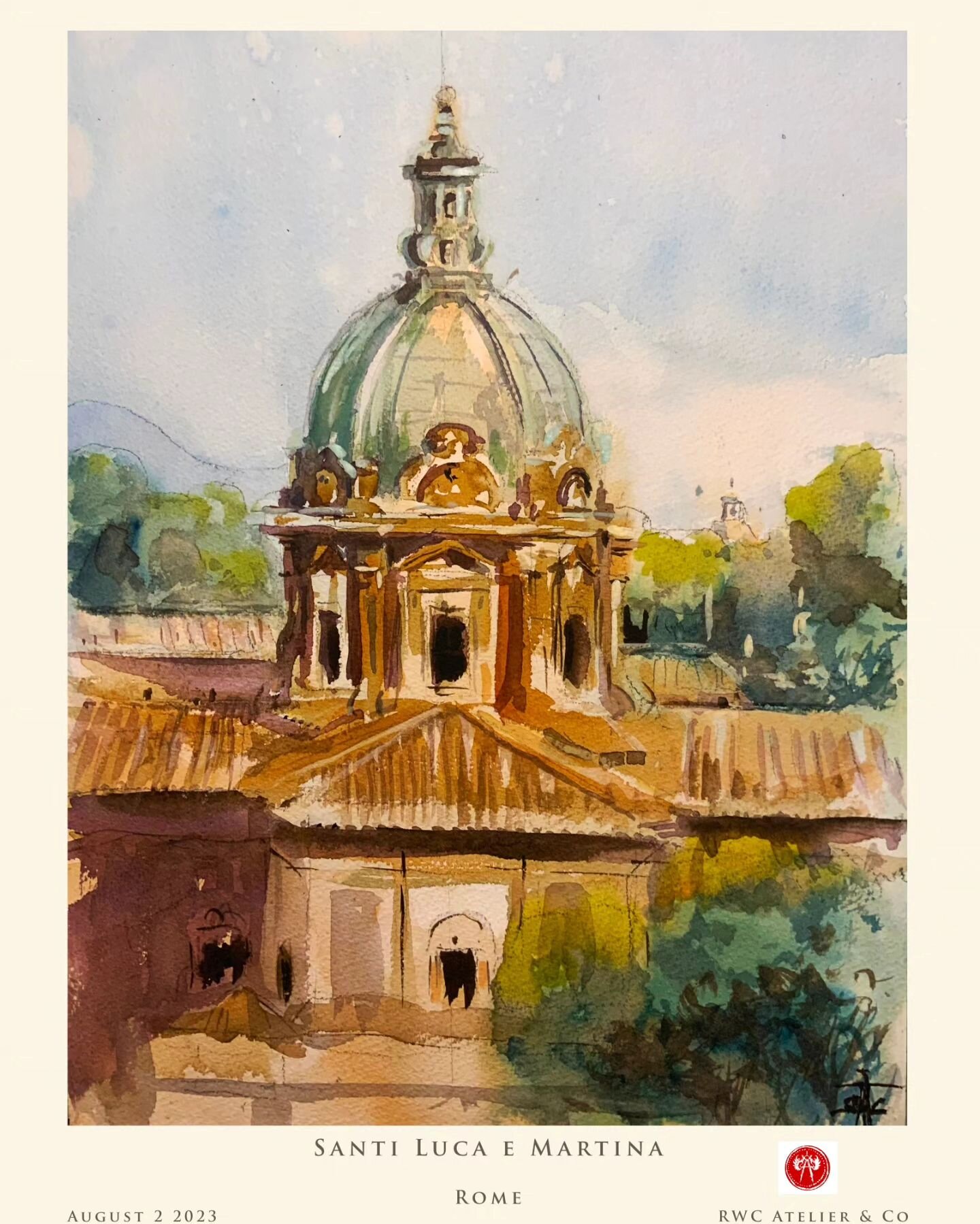

Now, return to the two paintings depicted above; Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema's painted works are indeed also architectural works, ones that we move through, inhabit with our mind’s eye.

Below is a painting by Alma-Tadema’s daughter, Anna (1865–1943), who would become an accomplished painter in her own right, depicting one of the rooms in her father’s house.

See more on Alma-Tadema as a witness to history here: