by Michael Djordjevitch

Given my previous discussion, compactly foregrounding the Classical in Architecture, what follows should be self-evident.

The question addressed here is, Why are the columns in the Great Hall of New York's Penn. Station so Indispensable?: that is, why No design in Any of the "modern" idioms would, or Could, be an Adequate substitute.

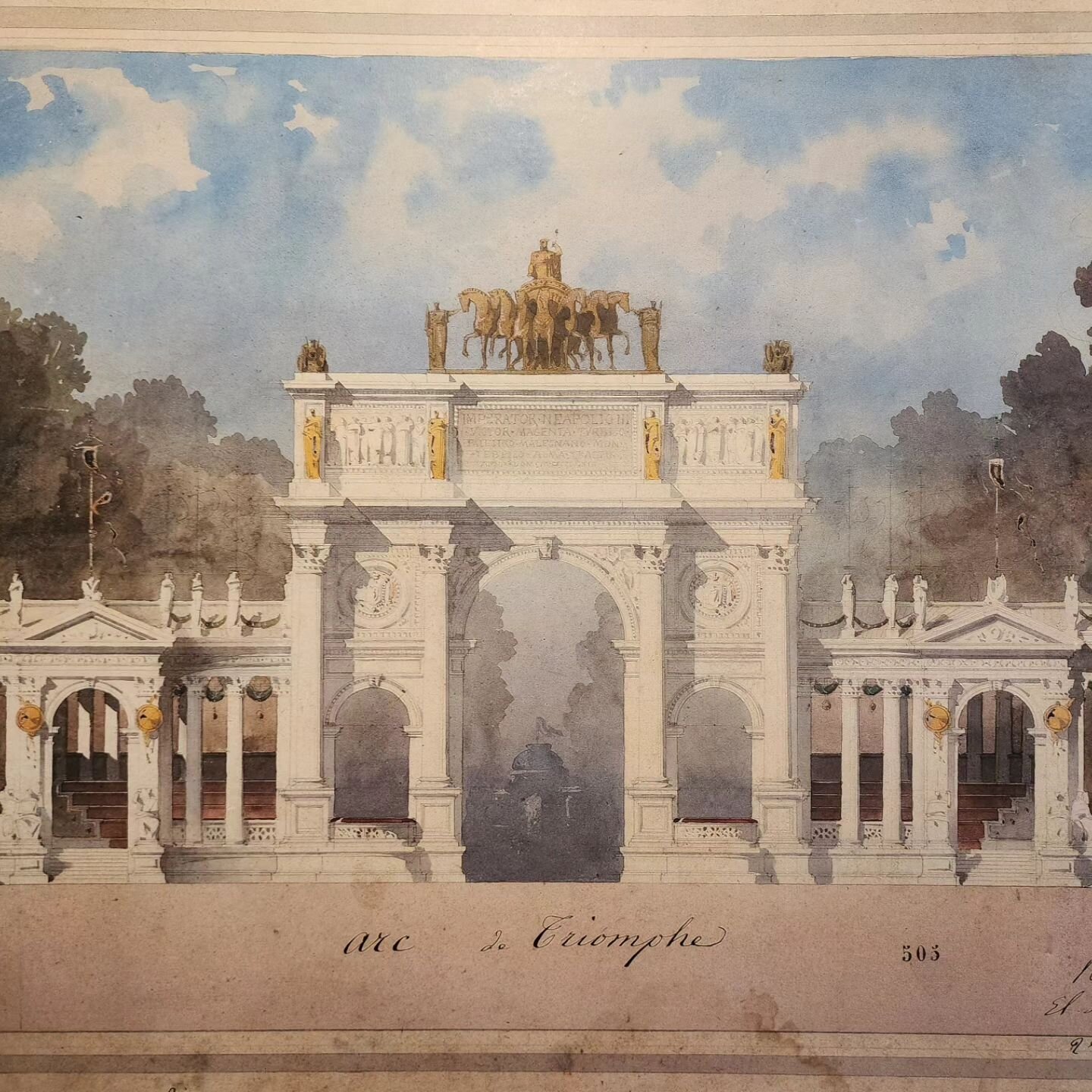

The first image, is from a set-design by Charles Percier, Pierre Fontaine, and Jean Thomas Thibault: the play “Elisca, or Maternal Love,” produced in Paris in 1799 (Act I). This drawing is currently on exhibit at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery in NYC. While channeling Eighteenth-Century speculations on the Origins of Architecture, the image's artistic presentation of them transcends their crippling utilitarianism. In foregrounding The Tree, as standing in-between, between the earth and the sky, this Painting foregrounds that Iconic part of the natural world which most Poetically resonates with Our shared condition, Plato's Metaxy: of Also, always and everywhere, living In-Between.

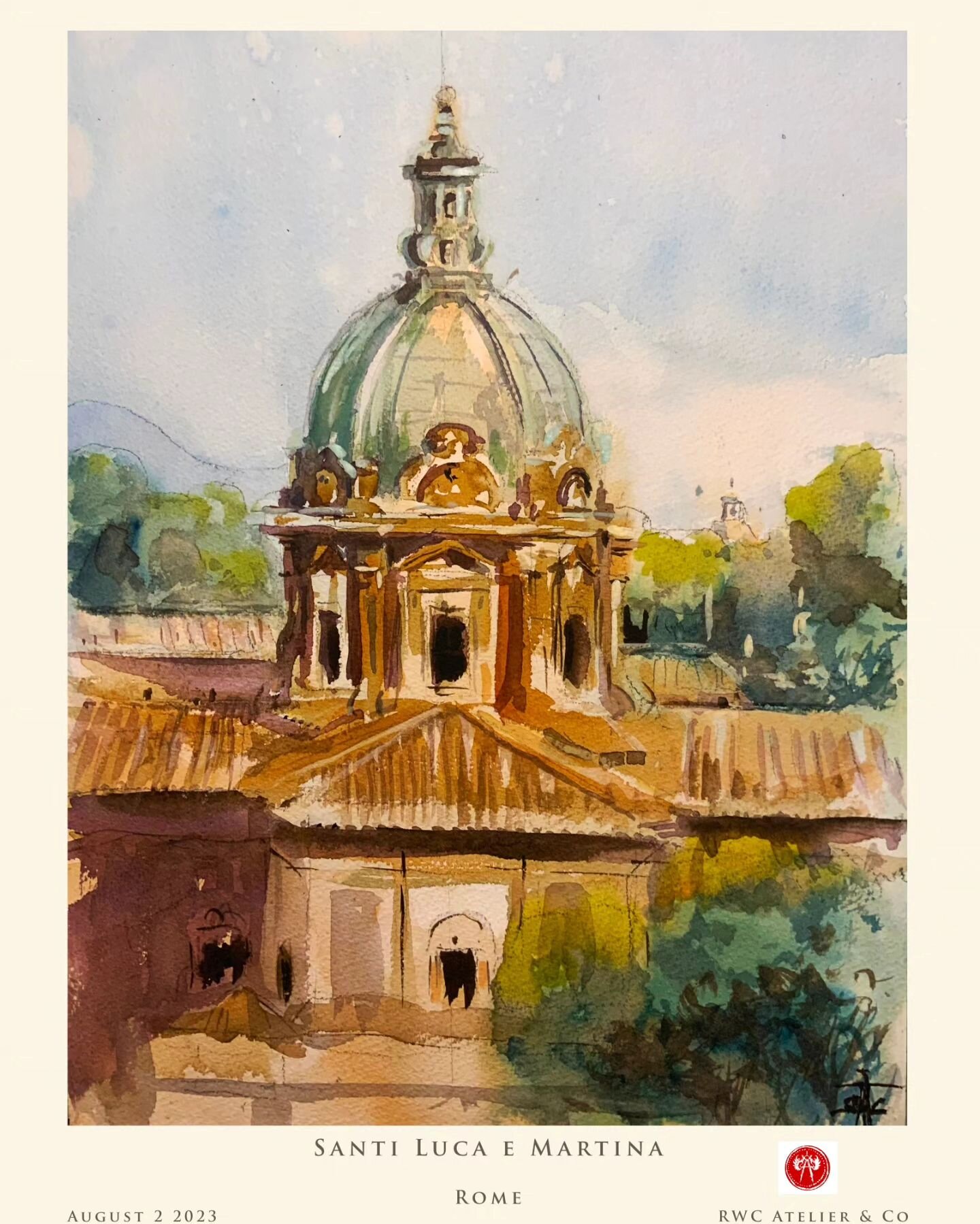

It is no accident then, that the prototypical Tree, whether for the Minoans, the Egyptians, or for their Heirs, the Classical Greeks, is a shared fundamental Icon. This embodied-through-Architecture Icon, in the fullness of its cultural meaning, is first encountered, in our human unfolding, in those paradigmatic Pyramids of Egypt.

Thus, when we encounter Great Columns in Charles McKim's splendid Great Hall at New York's Pennsylvania Station, they resonate, powerfully, to us as human-beings, no matter our particular cultural formation. Through our schooling, we have been taught to believe that columns, in architecture, support. And, of course, they do so, as elements of a Construction.

But, lets pause for a moment, and take in this Great Hall of Charles McKim's. What are these Great Columns, here, Actually doing?

They are doing exactly what they were doing in McKim's Roman prototypes, anchoring the billowing vaults. To put it a bit differently, we do not Feel the great vault Pressing Down on these vast columns: rather, the opposite. The columns are strangely stretched, yet balanced, between the vault and the ground.

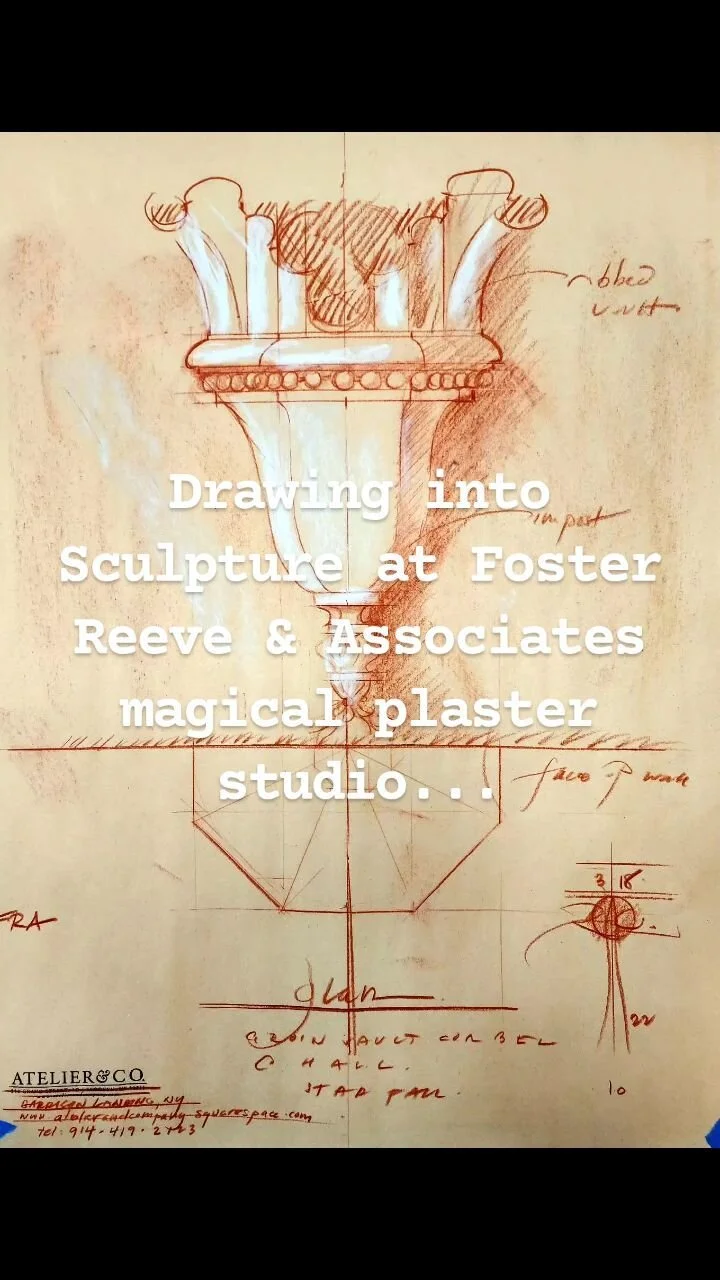

For a nuanced discussion of all this first turn to Geoffrey Scott's "The Architecture of Humanism." Leon Battista Alberti, in his "De Re Aedificatoria" offers these striking observations: that the Column, as a Sculptural Form Is The Very Chief Ornament of Architecture; further, that it is through Ornament, as such, that Beauty "shines forth." Thus, the sculptural form of the Column is therefore intrinsic to Architecture, as such, in the fullness of its meaning.

Beyond the Great Hall at Penn. Station are the even more overtly billowing glass and steel vaults of the great Train Hall. And, of course, while less sculpturally articulated, they are spontaneously read In-Context: that is, the more compact is seen in the light of the more articulated.

And let us not overlook the monumental light-standards within the Great Hall. They very much stand as intermediaries between the great columns, and us; a kind of sculptural Grove.

For Alberti, even more overflowing with Beauty, than the Column, is The Statue. In Context: in Alberti, the Column stands as that Part of Architecture which most fully embodies its reality, as an Art, existing in-between the Arts of Sculpture and Painting on the one hand, and the Arts of number and geometry on the other. Thus the Orders: each, always, as one-of-five, capture, foreground, and embody that spectrum between the figural and the numeric/geometric which is the Realm of Architecture (much more on all-this in later postings).

There are two Sculptures at the Threshold of the Great Hall. The Hall, and the Station overall, could use more. Dominique Papety's lovely painting of 1839, "Les Femmes à la Fontaine", in the Musée Fabre, is a vivid Treatise through the Visual on the above.

Little further, then should need to be said about our non-classical offerings. The two stand for the utilitarian and the expressive. The first would be even more banal and oppressive in reality than the images suggest. The second, a giant sculptural reification of frantic movement would be even more oppressive.

Our closing image is that of another stage-set, this one for a film starring Judy Garland, in which our Great Hall played a role. Let it stand for the ever haunting Platonic Form of McKim's Great Station awaiting its re-birth in the here and now, so that once again, travelers from the south may enter this Great City as beings which reach for the sky rather than ones which burrow into the depths of the earth.